Most shepherds have probably heard of OPP as it is one of the three diseases included in the biosecurity panels that many laboratories offer. The USDA Sheep 2001 study tested over 21,000 samples from 682 randomly selected flocks country wide to collect data on the prevalence of OPP. They found that 36.4% of flocks had one or more animals that tested positive and overall, 24.2% of the animals tested were positive for OPP. Only 1.2% of the producers suspected that their animals were infected with OPP. This data is from over 20 years ago but still relevant as it shows a disease picked up in 1 out of 4 randomly sampled sheep, in 1 out 3 flocks and their shepherds were not aware that the disease was present.

OPP must not be an economically important disease if most shepherds don’t even know their sheep were infected, right? Well, no, the short answer is that it depends on how lucky you are. There are many subtypes of the virus and they differ in how severely infected animals are affected. The genetic susceptibility of the exposed animals also plays a large role in determining if they get infected and how soon, as well as the degree of disease that they exhibit.

There is controversy on the economic impact of OPP. Some studies have shown no difference in the production of ewes that test positive for OPP compared to negative ewes in the same flock, while others have shown a profound effect. The testimonials of shepherds that have eradicated OPP from their flocks have shown major improvements once free of the disease. The OPP society (https://oppsociety.org/library/) has multiple personal stories from shepherds that have successfully eradicated the disease.

OPP is caused by a Small Ruminant Lentivirus (SRLV). This virus is in the Retroviridae family and Lentivirus genus and shares this genus with the viruses that cause HIV in people, FIV (Feline Immunodeficiency Virus) in cats and EIA (Equine Infectious Anemia) in horses. SRLV causes OPP in sheep, known as Maedi-Visna (MV) in other countries, and Caprine Arthritis-Encephalitis (CAE) in goats. There is a lot of genetic diversity in SRLV with many subtypes that can infect both sheep and goats. Not all subtypes cause severe disease and some are more pathogenic in sheep and others in goats. The virus causes lifelong infection, typically replicates slowly and usually only causes clinical disease in sheep that are over two years old.

Clinical Signs

Clinical signs develop slowly and therefore older animals are much more likely to show signs of disease. SRLV has an affinity for monocytes and macrophages. Monocytes are a type of white blood cell that circulate in the bloodstream and then migrate into tissues and mature into macrophages. Macrophages are tissue white blood cells that fight infection and clean up dead tissue cells in the organs where they reside. These infected macrophages produce more virus and cause chronic inflammation in the affected organs. Chronic inflammation, over time, leads to an increase in lymphocytes in the affected organs and eventually to the replacement of normal tissue with lymphoid tissues that do not perform the normal function of the tissues that it replaced. These “lymphoid infiltrates” also take up space that impedes the normal functioning of the remaining normal tissues. Different symptoms can be seen depending on the organ(s) that are affected in a particular animal. Remember, animals can replicate and spread infection before they become visibly ill.

Hard Bag

An udder that looks large, like a ewe that is lactating and has ample milk but feels hard and produces very little or no milk. These udders are not hot, red or painful. The milk producing tissue gradually is replaced by lymphoid tissue so your younger ewes might still produce well but after one or two lactations are not able to raise lambs anymore.

What you’ll see: More bottle lambs, more lambs that die of opportunistic infections due to insufficient colostrum, lower lamb weaning weights and more ewes being culled at younger ages for udder issues.

Thin Ewe Syndrome

Animals with normal appetite, which appear healthy, but lose weight or are not able to regain body weight after weaning their lambs due to chronic inflammation.

What you’ll see: More ewes are culled at a younger age for inadequate body condition.

Lungs

Ovine progressive pneumonia is a lymphocytic interstitial pneumonia where the connective tissue in between the airways is infiltrated by lymphocytes and enlarges. This impairs normal breathing as the lungs cannot collapse fully on exhalation and cannot fully expand for inhalation. Affected ewes are more prone to other pneumonias. On postmortem you can see lungs that feel firmer and do not collapse as normal lungs do.

What you’ll see: Ewes that breathe faster at rest and ewes that fall behind when moving the flock. More ewes dying during hot weather or when heavily pregnant and more pneumonia. Increased ewe death or culling due to pneumonia or inability to keep up with the flock.

Arthritis

Chronic inflammation in joints leads to damage to the cartilage and swelling of the joints. This can be quite debilitating to the ewes, especially if they are heavily pregnant. Ewes with sore joints do not compete at the feed bunk and are more prone to pregnancy toxemia.

What you’ll see: Arthritis in ewes in their prime.

Nervous System

The brain, spinal cord or individual nerves can be affected.

What you’ll see: Stumbling and incoordination that can progress to paralysis. Other diseases can cause similar signs but this will not respond to treatment.

OPP can affect older animals with symptoms that we associate as “normal wear and tear” from years of producing lambs which can make it less likely that producers suspect the disease is present in their flock. Typically, flocks will see more ewes being culled at a younger age (for udder and body condition issues), more bottle lambs, more lambs dying in the first week of life, more adult animals affected by lung issues (exercise intolerance, pneumonia). When aggressive strains are introduced to a farm and most of the sheep are genetically susceptible it can lead to severe economic losses, while a mild strain in a flock of resistant sheep might not have a significant effect.

Stressors can lead to an increase in infected animals suddenly becoming symptomatic. A very bad parasite year or drought, leading to nutritional inadequacies, can cause a large proportion of animals in an OPP infected flock to progress to clinical disease.

How does it spread?

The good news is that you need close contact between an infected sheep or goat and your flock to introduce this disease. The bad news is that it will likely walk onto your farm in an animal that you just paid good money for. Infected, asymptomatic animals are very capable of spreading disease. It is mainly spread through respiratory secretions, and social distancing of at least 10 feet between animals should prevent spread. It spreads much more in flocks housed in barns than flocks that are outdoors year round.

Once you have the virus on your farm it spreads among the flock mainly by respiratory secretions but can spread through other routes too. Infected dams can spread the infection to their lambs, mainly through colostrum and milk. About 30% of lambs born to infected dams will be infected. Some eradication programs recommend removal of lambs before they can suckle and artificially rearing them to prevent infection. There is also a very small chance of in utero infection of lambs. Studies have shown that the majority of infections spread via respiratory secretions though, so artificial rearing is not essential for eradication programs.

The virus does not live long outside of an animal, (it dies within minutes outside) so in general you do not have to worry too much about spread via inanimate objects. Objects that are used on multiple animals in a short time period like drenching guns, vaccinators or ear taggers can, however, spread the disease between animals.

Remember, any infected animal can spread the disease, they do not have to show signs of the disease to spread the virus.

Diagnosis

Antibody testing

OPP is usually diagnosed by antibody testing on a blood sample. There are many different ELISA tests available from multiple laboratories. Pricing is in the $4-$7 range, depending on the lab, and most offer a discount if you test large numbers of animals. Individual SRLV testing as well as combination OPP/Johnes/CL biosecurity screens are available.

A positive test shows that the animal is infected by a SRLV. It might take years to get sick or, if infected with a very virulent strain, they could succumb to the disease in a short time.

This test looks for antibodies to the virus. When the animal is first infected they will test negative as they have not yet had time to make enough antibodies to be detected by the test. Ideally you want to test an animal multiple times, separated by at least 60-90 days to be sure that they are not incubating the disease.

Can you have a false positive or negative test? Yes, it can happen. No lab test is 100% sensitive and specific. All laboratory tests have specificity and sensitivity ratings. A test that is 100% sensitive will give a positive result for all infected animals; no positive animal will test negative. A test with 100% specificity will give a negative result for all the animals that do not have the disease. No animals that do not have the disease will test positive. All labs should be able to give you the sensitivity and specificity for the test that they use. The closer to 100% for both, the better. For example, the c-ELISA test at WADDL has a 95% sensitivity and 98.4% specificity for sheep. This means that 5 out of 100 animals will test negative when they really are positive and 1.6 out of 100 animals will test positive when they really are negative. Retesting at another laboratory after waiting a few weeks could give a different result. In ewes, vaccination with Chlamydia vaccine has caused false positive results that reverted back to negative a few months later. The Elitest offered by the University of Minnesota does have fewer false positive results as can be seen in this study https://oppsociety.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/vmrd-cross-reactivity-poster-patnayak.pdf

PCR testing

PCR tests detect the actual virus in blood. It is a much more expensive test ($35) and generally not used as a screening test for multiple animals.

More detailed information on testing for OPP is available here https://oppsociety.org/opp-testing/

Necropsy

Animals that die due to lung involvement from OPP have distinctive lungs that do not deflate. Histopathology on affected organs will confirm the diagnosis.

Whole flock antibody testing is a good way to know that the disease is not present in a flock. A single animal can have a confounding test result if they are incubating the disease. Testing a large percentage of the flock, especially repeatedly at intervals of months or years, can give you confidence that the flock is free of OPP.

Prevention

Biosecurity

As long as your flock is not already infected, you can keep your sheep that way by never introducing any sheep or goats to the farm again. Unfortunately, most of us need to introduce new genetics from time to time and therefore need a plan to keep the virus out.

Make sure you have good perimeter fencing to keep stray sheep and goats away from your flock.

Quarantine new arrivals, at least 10 feet away from the resident sheep. Make sure your quarantine pens are escape proof. Sheep do not like to be alone so be sure to provide a friend. Make sure your “friend” is an animal that you will not mind culling if you find disease in your new arrival. A meat lamb is a good choice. On the flip side, if you do not know the OPP status of your flock, it is possible to infect your new arrival while in quarantine if the “friend” is OPP positive.

Test new arrivals for SRLV upon arrival. If they test positive, you can wait two weeks and re-test them to make sure it was not a false positive (a VERY small chance of that). If they are still positive on retest, cull. If you are neurotic like me, you cull them right away as Murphy’s Law says, they will break out in the next two weeks and go visit your ewe flock.

The reason for the test upon arrival is so that if the animal comes already infected and tests positive, you can cull right away and not waste quarantine time and effort.

If your new arrival passes the first test, then retest again, 60-90 days later. There is variability in the incubation period for OPP, because the virus “hides” in white blood cells. Some animals can have extended incubation periods but the Elitest ELISA antibody tests claim that they can pick up the infection between 12 and 52 days after infection.

Keeping an animal in quarantine for 60-90 days is asking a lot. You have to plan far in advance if it is a ram you plan on using for breeding. Having animals in quarantine is also a pain and the longer you need to do it, the more tedious it gets. Repeating blood tests cost money.

The reason for the retest is that the initial test will be negative if the animal has only recently been infected. Animals that are purchased at sales (lots of other animals stressed by traveling far) or that hitched a ride to your farm along with other animals from different farms (we are all doing this; gas is EXPENSIVE!) are more at risk of having just picked up the virus and having a negative test on arrival. They have just not had it long enough to have sufficient antibodies to have a positive test upon arrival.

Buying off the farm, from a breeder that does whole flock testing for OPP and is willing to show you their negative test results, and not having the animal travel with sheep/goats from other farms lowers the risk of introducing OPP to your flock significantly.

Genomic testing

Initially it seemed like some breeds of sheep were more resistant to OPP and that other breeds were super susceptible to the disease. However, once they started looking into the genetics of OPP resistance, it turns out that the more resistant breeds have more individuals with resistant genotypes and the opposite is true for the susceptible breeds.

Most sheep breeders are familiar with genetic resistance to Scrapie. Selection for sheep that are RR or QR at codon 171 produces sheep that do not get classical Scrapie. Unfortunately, genetic resistance to OPP is not as straightforward as Scrapie resistance. Genetic resistance to OPP is not bulletproof. “Resistant” animals that live in flocks with high exposure will still get infected, it just takes longer and they are not as severely affected.

Genetic markers for OPP resistance are found on the TMEM 154 gene. There are 15 haplotypes with 1-4 being the most common, and each sheep has two copies (diplotype), so your genomic testing will give a TMEM154 diplotype result such as TMEM 1,1 or 1,2 or 2,3 etc.

Among the common haplotypes there are two “resistant” haplotypes (1 & 4) and two susceptible haplotypes (2 & 3). Unfortunately, the susceptible haplotypes are dominant so you need two copies of resistant haplotypes to be “resistant”. Therefore OPP “resistance” is only present in sheep that are TMEM 154 diplotypes 1,1 or 1,4 or 4,4.

In animals that are TMEM 154 4,4 this diplotype totally turns off this gene. As they do not know exactly what the protein produced by this gene does, it is not recommended to select for this genotype. It is recommended to select for TMEM154 1,1 diplotype to breed sheep with OPP “resistance”.

Breeding in OPP “resistance” is harder to do than Scrapie resistance where having just one copy of the R genotype imparts resistance. With Scrapie, regardless of the genotype of your ewes, a RR ram will give you scrapie resistance in the first generation, even if all your ewes are QQ, as all lambs get one copy of the gene from each parent and the ram only has R genes to pass along, so all your lambs will be at least QR.

For OPP “resistance”, if your ewes do not have any copies of the 1 or 4 haplotypes, then breeding them to a ram with 1,1 diplotype will produce offspring with one copy of the resistant haplotype but they will still be susceptible to OPP. If you continue breeding their offspring to 1,1 rams the next generation will start having some lambs with TMEM 1,1 diplotypes and actual OPP “resistance”. You can definitely still breed in “resistance,” it just takes longer. If you have genotyping available on your ewes too, you will be able to make faster progress.

USMARC did three studies comparing ewes with different TMEM 154 haplotypes and how they responded to living in an OPP infected flock. They compared haplotype 1 to 3, haplotype 2 to 3 and haplotype 1 to 4.

- TMEM 1,1 haplotype ewes were compared to ewes with 1,3 and 3,3 haplotypes, living in an OPP infected flock. 80% of the 1,3 and 3,3 ewes were infected by the time they were 3.3 years old vs only 10% of the 1,1 ewes being infected by the time they were 5.5 years old.

- The 1,1 ewes weaned on average 2.1 more lambs and 40kg (88 pounds) more weight of lambs over the 5.5 year experiment when compared to the 1,3 and 3,3 ewes.

There is definitely benefit to selection for OPP “resistance” through selection for TMEM 154 1,1 diplotype BUT it is important to note that it does not 100% prevent infection and therefore should be combined with biosecurity and testing to manage and prevent OPP in sheep flocks.

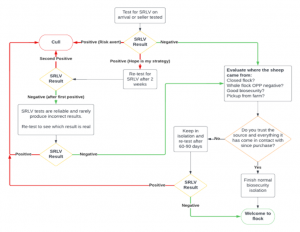

Whole flock testing

So, I made you curious about the OPP status of your flock? Good. How do you go about finding out where you stand? If your flock is small or if you can afford it, test all your animals. You can, however, sample only a portion of your flock and still be reasonably certain using the chart below (there is a 95% chance of catching a positive animal if at least 5% of your flock is infected). It is important to only test animals over one year old. Do not cull all the ewes with signs suggestive of OPP and then test the flock. If you go to the trouble of testing, why not make sure that you will find the positive ewes if they are there?

![]()

Hopefully, you will get a “whole flock” negative test. Great!! You are probably OPP free. Best practice requires two whole flock (or portion of flock per table above) negative tests separated by at least six months, and ideally one year. Make sure that you have excellent biosecurity in place to keep it that way. Show your test results to breeders that ask about your flock status and be ready to discuss what biosecurity practices you have in place to prevent introducing the virus.

I have OPP in my flock, now what?

You did whole flock testing and expected everyone to come back negative, but the test results show otherwise, what now?

Only a few animals test positive

Great, aren’t you glad you tested? You can cull those animals and prevent them from spreading it to the rest of your flock. At this level of infection, it is recommended to cull lambs of ewes that test positive too. Look at your biosecurity practices and see what you can do to prevent re-introduction. If you only did a partial flock test, be sure to test all your sheep. You have a low prevalence of infection and probably did not find all the positive animals.

When did you last introduce animals to the farm? If within the last few months, you should re-test sooner as it is more likely that you have infected animals that just do not have enough antibodies to test positive yet. The longer you leave infected animals in the flock the greater the chance of them spreading the infection. If it has been six months or more since introducing new animals you can probably wait longer to re-test as infected animals should have had enough time to develop antibodies. Re-test your flock in six months and, if everyone is still negative, re-test in one year. If follow-up testing is negative, Congratulations, you have eradicated OPP from your flock!! Make sure to review your biosecurity to make sure you do not re-introduce the infection.

You now have an OPP test negative flock. I am sure the experience of having had OPP in your flock has made you more careful about avoiding introducing it again. I will gladly buy from you.

Yikes! Half my flock (or more) is positive

You can decide to just live with OPP; hopefully you have a mild strain and genetically resistant ewes. If not, keeping a profitable flock might be a challenge. Just be sure that you disclose this to buyers; not just breeding stock but also cull ewe and feeder lamb buyers as these buyers often keep the animals on their farms for a time to finish them and have breeding stock of their own. Look into genetic testing for TMEM 154 or make sure that you use rams with TMEM 154 1,1 haplotype to breed ewe lambs that will be more productive in an OPP infected flock. Keep your sheep outdoors as much as possible to reduce the further spread of infection in your flock.

You can sell out and restart your flock, but selling ewes as culls and replacing them with premium breeding stock is an expensive endeavor and enough to put many producers out of business. You can just cull all the positives, but how are you going to stay in business with only half your flock? Fortunately, you have options to build a negative flock out of a heavily infected one. Sheep breeders have done it, but you need to be committed to doing it right as cutting corners will still be expensive and not give you good results. You can keep your infected ewes as long as they are productive, and start working on a negative flock out of your retained test negative ewe lambs.

Here is how to work your way up to a negative flock:

- Keep all your ewes in one flock together, regardless of whether they tested positive or negative. About 30% of the spread of OPP is from the ewe to her lambs, but 70% of the spread is from one sheep to another.

- Ewe lambs are born in the infected adult flock and stay with the adults and are suckled by their dams until weaning at 60 days old.

- After weaning, the ewe lambs are kept separate from the adult flock by at least 10 feet and preferably housed outdoors.

- Ewe lambs are tested at 6 months old; positives are culled and negatives are the start of your new OPP negative flock. They NEVER have contact with the adult flock after weaning. If you cannot do this reliably, this process will not work.

- Each crop of lambs is raised the same and the negative testing ewe lambs are added to your negative flock. As your negative ewe flock grows you can gradually cull out your original positive flock.

- Look into genetic testing for TMEM 154. You can have a much more productive flock if you incorporate OPP resistant genetics.

This will be expensive (you need to test all the ewe lambs) and management will be difficult as you need to make sure that the two groups do not mix; otherwise, all your efforts will be wasted. It can and has been done successfully as part of the Minnesota OPP eradication scheme. You can read their stories at the OPP society web page.

On a personal note….

We introduced OPP into our ram flock this year. The photo above is our ram flock. Only the two brown boys tested negative. We tested all our ewes and are very fortunate that the infection was contained in our ram flock. All incoming rams tested negative upon arrival at the farm but one must have been incubating the disease. Six out of eight rams tested positive, so it quickly spreads between animals that live together. Thankfully our rams do not share a barn with the ewes over the winter, so they did not pass the infection to the ewes. All but one of the rams were with the ewes in October and early November last year. Since none of the ewes were infected, the rams must not have been contagious at that time, or it came in with the ram that arrived after breeding ended. OPP can spread quickly, 75% of our ram flock was infected in a seven-month period.

We introduced OPP into our ram flock this year. The photo above is our ram flock. Only the two brown boys tested negative. We tested all our ewes and are very fortunate that the infection was contained in our ram flock. All incoming rams tested negative upon arrival at the farm but one must have been incubating the disease. Six out of eight rams tested positive, so it quickly spreads between animals that live together. Thankfully our rams do not share a barn with the ewes over the winter, so they did not pass the infection to the ewes. All but one of the rams were with the ewes in October and early November last year. Since none of the ewes were infected, the rams must not have been contagious at that time, or it came in with the ram that arrived after breeding ended. OPP can spread quickly, 75% of our ram flock was infected in a seven-month period.

We are culling eight rams (I hope they will make good sausage – it will definitely be the most expensive sausage I have ever had). We are not selling any breeding stock this year, have already spent a thousand dollars on testing and have two more rounds of testing coming up later this year and next year. With all of that we still feel very grateful that we dodged the bullet and did not introduce the disease into our ewe flock. We usually graze our lambs with the rams after weaning and found out just before weaning so we did not expose our lamb crop to OPP. While waiting on the test results for the ewes we went through all the scenarios of how much more work it would be to manage two ewe flocks (and probably two ram flocks as I would not want to infect a ram by using him on the positive ewes) out on pasture and in the barn over winter (we would have to build another structure), and how expensive it would be to do all the required testing (we lamb over 150 ewes each year).

We found one positive ram when doing routine biosecurity screening for rams we planned to put in a sale. We hoped for a false positive test (even though the odds were really low) and thought it a good idea to test the whole ram flock. We definitely did not expect to have 75% of them test positive as they all look healthy and happy. We are still grateful that we found it in the rams because it was a wakeup call. OPP always seemed like such a theoretical disease. I thought we had good biosecurity, but it turns out one negative test and 30 days quarantine is not enough. Is it a benign strain that we have? Maybe. But the rams are mostly yearlings, so maybe they are just not symptomatic yet. I definitely do not want to take the chance of infecting our ewe flock to find out. We will keep testing the ewes and as long as everyone stays negative, we can hopefully have a “whole flock negative” tested flock for OPP by next year.

We all have differing degrees of concern about disease in our flocks, how we like to do things and what we are willing to do. This cautionary tale shows how easy it is to introduce this disease and I hope I planted a seed to get more producers thinking about and testing for OPP.

By: Isabel Richards, Gibraltar Farm

EAPK Communications Committee

References

OPP prevalence

https://oppsociety.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/usda-opp-update-2003.pdf

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1686233/?page=1

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1263463/

Shepherds that have eradicated OPP

https://oppsociety.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/bredahl-heavy-burden-shepherd.pdf

https://oppsociety.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/opp_summer_2014_update.pdf

Subtypes of OPP

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8708130/

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3738966/

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8467527/

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3123287/

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1900236/

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0042682205003417?via%3Dihub

OPP eradication

https://www.bah.state.mn.us/media/opp-eradication-trial.pdf

TMEM 154 OPP genetics testing

https://oppsociety.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/opp-summer-2015-update.pdf

https://oppsociety.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/summer_2013_update.pdf

https://oppsociety.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/murphy-tmem154-productivity-2021.pdf

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4140605/

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3717717/

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4349320/

Mechanisms of OPP infection and disease progression

https://www.vetres.org/articles/vetres/pdf/2006/01/v6011.pdf

https://oppsociety.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/horizontal-transmission-productivity-study.pdf

https://oppsociety.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/opp-controversy.pdf

![]()