Scours or diarrhea is something that most of us probably see in our flocks over the course of a year. Animals scour whenever there is a disturbance in the normal processes that regulate how much fluid is excreted in their manure. Scours is a symptom, sometimes due to a serious disease that requires prompt treatment, but often diet induced and transient, requiring only tincture of time to resolve. Diet plays a large role in manure consistency; expect looser manure for a few days whenever there is an increase in protein and/or energy or a decrease in fiber in their diets. Sheep eating mainly grass hay will have dry pellets, while sheep on a high protein and/or energy or a low fiber diet will have much looser manure without there being a disease process at work.

Scours or diarrhea is something that most of us probably see in our flocks over the course of a year. Animals scour whenever there is a disturbance in the normal processes that regulate how much fluid is excreted in their manure. Scours is a symptom, sometimes due to a serious disease that requires prompt treatment, but often diet induced and transient, requiring only tincture of time to resolve. Diet plays a large role in manure consistency; expect looser manure for a few days whenever there is an increase in protein and/or energy or a decrease in fiber in their diets. Sheep eating mainly grass hay will have dry pellets, while sheep on a high protein and/or energy or a low fiber diet will have much looser manure without there being a disease process at work.

Wool sheep that scour can get flystrike and that makes prevention and aggressive treatment of scours much more important. We are fortunate that Katahdins tend to not have thick breech hair/wool during the times of year when scours are most prevalent.

There are limited ways in which excess fluid ends up in manure to cause scours. Please bear with me as we cover some terminology related to how fluids move in the body, as well as some gastrointestinal tract (GI tract) anatomy and physiology. Understanding these concepts and mechanisms will make it much easier for you to evaluate a scouring animal and decide how to intervene.

Anatomy, Physiology and Terms

Fluid movement into and out of the GI tract

The GI tract is lined with cells that absorb nutrients, electrolytes and fluid, and also secrete electrolytes and fluids into the GI tract according to the body’s needs.

Osmolality is a measurement of the concentration of dissolved particles (electrolytes, proteins etc.) in a fluid. Fluid moves from areas with low osmolality to areas with high osmolality.

Osmosis is the mechanism that moves fluids between body fluid compartments (bloodstream, interstitial space, etc.) to where they are needed. During this process fluid moves through a membrane in order to equalize the osmolality on both sides of the membrane.

Looking at the movement of fluid between the GI tract and the bloodstream:

- The main osmotically active particle in the blood is albumin, a protein. Electrolytes (salts) like sodium, potassium, chloride, etc. also play a role.

- Food that has been digested but not yet absorbed as well as electrolytes are the main osmotically active particles in the GI tract.

Isotonic

GI contents have the same osmolality as blood and will not draw extra fluid into the GI tract.

Hypertonic

GI content has high osmolality and will pull fluid from the bloodstream into the GI tract and lead to scours.

Hypotonic

GI content has low osmolality and fluid should be absorbed from the GI tract into the bloodstream.

Interstitial Space is the area between small blood capillaries and the cells that they deliver nutrients and oxygen to. This space is filled with interstitial fluid. The amount of interstitial fluid expands and shrinks to equalize the osmolality of the blood.

Fluid moves between the bloodstream and interstitial space via osmosis all over the body.

Looking at the fluid movement between the bloodstream and interstitial space:

- The main osmotically active particle in the blood is albumin, a protein. Electrolytes (salts) like sodium, potassium, chloride etc. also play a role.

- The main osmotically active particles in the interstitial space are dissolved nutrients and electrolytes.

Isotonic

blood has the same osmolality as the interstitial fluid and will not draw extra fluid into the interstitial space.

Hypertonic blood has high osmolality and will pull fluid from the interstitial spaces into the bloodstream. Dehydrated animals have very small interstitial spaces, which is why their skin is less elastic and their eyes appear sunken.

Hypotonic blood is usually due to low albumin (hypoalbuminemia) and has low osmolality. Fluid moves from the bloodstream into the interstitial space and causes edema. We see this as bottle jaw, swollen feet, brisket edema etc.

Maldigestion and Malabsorption

Maldigestion is when feed is not digested, usually due to a lack of digestive enzymes, changes in bacterial flora, or damage to the GI tract.

Malabsorption is when digested feed is not absorbed out of the GI tract. The further feed travels through the GI tract, the fewer nutrients it should contain. Having all these unabsorbed nutrients in the GI tract makes the GI content hypertonic. Hypertonic GI contents lead to fluid being pulled into the GI tract and causes scours. These animals lose weight over time or do not grow well as they are not absorbing enough nutrients. They do not absorb sufficient protein and become hypoalbuminemic which leads to edema. These animals often have scours, bottle jaw and weight loss.

pH

pH is a scale to measure if a liquid is acidic or basic. Low pH fluids are acidic (stomach acid pH 2-3) and high pH fluids are basic (saliva pH 8-9). Neutral pH is seven (water).

Anatomy and physiology of the GI tract

Ruminants have developed a symbiotic relationship with rumen microbes (bacteria, fungi and protozoa) that enables them to utilize high cellulose feeds like grass. The microbes convert otherwise indigestible feeds into Volatile Fatty Acids (VFA) that the ruminants can use for energy. The VFA’s are absorbed in the rumen and do not require additional digestion. The microbes that die are digested further down the GI tract to provide additional nutrition.

The rumen flora that dominates the rumen and reticulum is dependent on the diet of the animal. It usually takes a few days for the flora to adjust to a change in diet. The pH of the rumen fluid affects the predominant organisms. Different organisms produce different fatty acids and some are more easily utilized than others. Rumination adds saliva to the rumen and helps to balance pH as saliva has a basic pH. Rumination also helps to break down feed into smaller particles for better digestion. Larger feed particles stimulate more rumination and slows down intestinal transit time. The rumen should have a neutral pH but can be slightly acidic in animals on high energy rations. Sudden changes to high energy rations cause rumen acidosis.

The rumen flora that dominates the rumen and reticulum is dependent on the diet of the animal. It usually takes a few days for the flora to adjust to a change in diet. The pH of the rumen fluid affects the predominant organisms. Different organisms produce different fatty acids and some are more easily utilized than others. Rumination adds saliva to the rumen and helps to balance pH as saliva has a basic pH. Rumination also helps to break down feed into smaller particles for better digestion. Larger feed particles stimulate more rumination and slows down intestinal transit time. The rumen should have a neutral pH but can be slightly acidic in animals on high energy rations. Sudden changes to high energy rations cause rumen acidosis.

Food is not sterile and there are a lot of bacteria and other microorganisms that play an important role in digestion that reside in different areas of the GI tract. Even though the GI tract is inside the body there is a gut-blood barrier that prevents unwanted organisms and allergens from entering the bloodstream, while allowing nutrients and fluids to pass through. The gut-blood barrier is mainly made up of epithelial cells, covered by a thin layer of mucous.

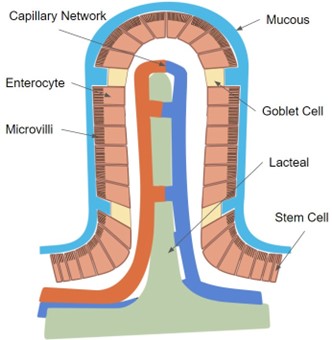

The main epithelial cells in the small intestine are called enterocytes. Each enterocyte has multiple folds in its cell membrane (microvilli) that extends into the GI cavity. The enterocytes are arranged into pillars (villi) that extend into the GI cavity and there are also cavities (crypts) below the GI tract surface that are filled with enterocytes. All of this works together to greatly increase the surface area that is available for absorption of nutrients. Enterocytes only live for a few days. The oldest ones are at the tips of the villi and new enterocytes are formed in the crypts and they mature as they move up the villi. Old enterocytes are sloughed off into the GI tract when they are at the end of their life. Anything that damages these cells and decreases the number of villi and microvilli will greatly reduce absorption of nutrients and lead to scours.

In between the enterocytes are goblet cells that produce mucus. The GI tract has a thin layer of mucus that sits between the enterocytes and GI contents which helps to protect the enterocytes from bacteria and viruses. Enzymes are also secreted into this mucus that help break down digesta into its smallest constituents to be available for absorption. The mucus also provides lubrication to help intestinal contents move through the GI tract without damaging the epithelial cells.

Digested proteins and sugars are absorbed directly into the capillary network in each villus, while fats are absorbed into the lacteals and enter the lymphatic system. The veins that drain blood from the GI tract go directly to the liver. The liver filters out toxins and processes the nutrients before the blood circulates through the rest of the body.

Fluids are pulled into the GI tract in the first part of the small intestine and then rapidly removed as the digested nutrients are absorbed as ingesta moves down the GI tract.

Most of the nutrients should be absorbed before ingesta gets to the large intestine (LI). The LI mainly absorbs a lot of fluid as well as electrolytes and some protein. Disease of the enterocytes in the LI interferes with the absorption of fluid and electrolytes and leads to scours. In animals with malabsorption a lot more digested material reaches the LI and pulls extra fluid into the GI tract leading to more severe diarrhea.

At the highest level, animals scour whenever there is a disturbance in the normal processes that regulate how much fluid is excreted in their manure.

- Water is passively absorbed from the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. It is pulled out of the GI tract along with nutrients and electrolytes that are actively absorbed.

- Water can be pulled into the GI tract to balance the concentration of electrolytes and nutrients between the blood and GI tract.

- Disease or damage to the lining of the GI tract will interfere with the normal absorption of water as well as the absorption of nutrients that will lead to excess water being pulled into the GI tract.

- When feed moves through the GI tract at a faster than normal rate, there is less time for nutrients and water to be absorbed, and this usually results in looser manure.

Causes of Scours

Microbes (Bacteria and Viruses)

As discussed previously, the GI tract is filled with bacteria, protozoa and fungi that are necessary for normal digestion. Pathogenic (disease causing) bacteria can be present but usually do not have a chance to reproduce out of control as the normal flora compete with them for resources. Disease usually occurs in animals that are immunosuppressed, have some disruption in their normal GI flora or are exposed to massive amounts of pathogenic bacteria or viruses in their environment.

E. coli:

Enterotoxigenic E. coli colonizes (attaches to and multiplies) the villi by directly attaching to the enterocytes. They release toxins that cause the enterocytes to secrete extra electrolytes into the GI tract, making it hypertonic and fluid is pulled into the GI tract to correct this. There is no inflammation associated with this, the enterocytes are not damaged and absorption is not affected. Affected lambs have very watery diarrhea and lose large volumes of fluid and electrolytes, leading to severe dehydration. Necropsy shows a normal appearing GI tract that is distended with fluid.

Enteropathogenic E coli (aka “attaching and effacing” E coli) also colonizes the villi and attaches to the enterocytes. They invade into and damage the enterocytes, “dissolving” the microvilli, greatly reducing the surface area available for absorption, as well as disrupting the normal absorption and secretion functions of the enterocytes. Because the enterocytes are damaged this can lead to sepsis as the gut-blood barrier is disrupted. Damage to the enterocytes causes inflammation and swelling of the GI lining that also interferes with normal function. Nutrients are not absorbed so animals lose weight and especially young lambs can succumb to hypoglycemia. Severe infections can cause ulceration and erosions in the GI lining and consequently bloody diarrhea and mucus. Lesions higher up in the GI tract (closer to the stomach) will cause black scours as blood is digested as it moves through the GI tract while lesions in the colon and rectum produce fresh, red blood in the manure.

Rotavirus & Coronavirus:

Both viruses invade the enterocytes to reproduce, and damage or kill the cells in the process. The damage and inflammation lead to a greatly decreased surface area for absorption of nutrients, causing diarrhea due to unabsorbed nutrients pulling fluid into the GI tract. Nutrients are not absorbed so animals lose weight and especially young lambs can succumb to hypoglycemia. Cells are damaged so diarrhea can be bloody and have mucus in it. Lambs can have a fever and act sick.

Clostridium perfringens:

Clostridium perfringens Type C produces a toxin that causes hemorrhagic enterotoxemia. Most often lambs are just found dead. If you find affected lambs before they die, they show abdominal pain, bloody diarrhea, weakness and depression. Other clostridium species and types can also cause scours. This can be a significant problem in bottle fed lambs and an important reason to make sure they stay up-to-date with their CDT vaccines.

Other:

Salmonella, campylobacter, yersinia and many other bacteria and viruses can also cause scours. Other GI bacteria that have “attaching and effacing” types can cause scours in the same way that E. coli does.

Most commonly, bacterial and viral diarrhea is seen in young lambs (birth to 2 weeks old). Lambs with scours can be affected by multiple species of bacteria and/or viruses at the same time. These lambs usually did not receive adequate colostrum and/or are housed in a way where they can ingest fecal material from other sheep. Young animals of all species explore the world by tasting it, so it is easy for them to ingest fecal material by chewing on bedding. Ewes’ udders can also easily be contaminated by fecal matter, exposing lambs when they suckle. Milk (and milk replacer) is a great medium for bacteria to grow in.

Older animals can get bacterial and viral scours but are usually not as severely affected as young lambs. There is usually an underlying issue that makes them susceptible to it, such as:

- Mineral imbalances that lead to suboptimal immune function;

- Antibiotic use

- Stress – inadequate nutrition, lambing, weaning, moving to a new farm, parasites;

- Overwhelming intake of pathogenic bacteria – contaminated feed or water sources, overcrowded living conditions and inadequate bedding.

Treatment:

These lambs do not have a lot of body reserves and might have had a tough start in life already. Mildly affected lambs will require a lot less time and effort but severely affected lambs require a lot of TLC and might still die regardless of your best efforts. If you have multiple lambs that are affected, get your veterinarian involved sooner rather than later as a severe outbreak can cause significant losses.

- KEEP UP HYDRATION. Dehydration can kill young lambs in a few hours if they have severe scours. Oral electrolyte solutions work well as long as they are started early. Solutions that have glucose in them will help to prevent hypoglycemia. If hydration cannot be maintained using oral rehydration, then IV fluids are required.

- Do not feed large amounts of milk or replacer at a time. It is OK to skip a meal if you are giving an electrolyte solution with glucose in it. Offer multiple small meals throughout the day rather than two large meals.

- Keep them warm.

- Keep them away from other susceptible lambs.

- Inject a serum antibody product like Bovi-Sera to boost the lamb’s immune response.

- THE MAJORITY OF THESE ORGANISMS CAUSE DISEASE IN PEOPLE TOO. Practice good hygiene when working with these lambs, they often have scours stuck to their fur and feet. These are not the lambs that your kids should be snuggling with.

- Provide probiotics. Ruminant specific probiotics are good but yogurt with live cultures or human probiotics can also be used.

- Antibiotic use is controversial. They are obviously not needed for viral infections and will kill off beneficial bacteria. There is also concern about inducing antibiotic resistance in these pathogenic bacteria and that animals that recover will become asymptomatic shedders. However, when the gut-blood barrier is affected, bacteria will enter the bloodstream leading to sepsis. Sick lambs with scours definitely need antibiotics but most likely mildly affected lambs that are still drinking, acting normal with normal body temperature probably do not need antibiotics. Be sure to watch these lambs though and do give antibiotics if they do not improve or if their condition worsens. Talk to your veterinarian about what the most appropriate antibiotic to use is. You want something that is injectable and that provides adequate circulating antibiotic levels to prevent sepsis. Oral antibiotics are absorbed but you might not get adequate blood levels in an animal with diarrhea as absorption is decreased. The antibiotic should target gram negative bacteria (most of these bacteria are gram negative) and be excreted through bile, so you will get adequate concentration in the GI tract too.

- Anti-inflammatories can help lambs feel better and reduce inflammation BUT they can cause kidney damage in dehydrated animals, so rehydrate them first before use. Anti-inflammatories can cause GI ulceration so be conservative in how often they are given.

Prevention:

Bacterial and viral scours are best prevented.

- Make sure adequate, clean bedding is available in the lambing area and jugs to minimize exposure to pathogenic GI organisms.

- Keep your ewes in good (but not too fat) body condition so they are able to produce a large enough quantity of good quality colostrum for all their lambs. Ewes that are healthy and receive adequate nutrition in late pregnancy are less likely to shed large amounts of pathogenic bacteria in their manure.

- Do not intermix lambs of different ages, this is especially important if you house groups of bottle lambs together. Try to have no more than 30 days between the youngest and oldest lambs in a pen. The older lambs are good shedders of pathogenic bacteria that they have built up a tolerance to while the younger lambs are still susceptible.

- Vaccinating ewes for CDT in late pregnancy will provide immunity to clostridial disease in their lambs.

- Make sure that lambs receive adequate volumes of colostrum within the first 24 hours of birth. Especially the smallest lamb(s) in a litter of triplets or quads might not receive a large enough dose. Ewes with udder edema might need to be milked out once or twice and the colostrum fed to their lambs to get their teat size small enough to allow lambs to suckle.

- For lambs that you suspect might not receive adequate colostrum, give a colostrum supplement in the first 24 hours. If you miss this window, give an injectable antibody supplement like Bovi-Sera or OVIShield to give them protection.

- Keep any scouring lambs away from other lambs until they have normal manure for 2-3 days. Giving them a bath before returning them will also help decrease bacteria in the environment.

- If you have multiple lambs affected in multiple lambing seasons in spite of addressing hygiene and colostrum intake, talk to your veterinarian about vaccinating your ewes in late pregnancy with one of the cattle scour vaccines. This will be off label use, be sure to consult with your veterinarian about the appropriateness for your flock, best time to vaccinate as well as withdrawal periods.

Parasites (protozoa and worms)

Cryptosporidium parvum:

Cryptosporidium is a protozoan parasite that can cause diarrhea in young lambs, mostly under two weeks of age. This parasite is very prevalent in dairy calves but usually not a common cause of diarrhea in lambs. Outbreaks have occurred though and can cause severe losses. This organism can affect people too, so practice good hygiene when handling infected lambs.

Lambs are infected by ingesting a sporocyst (the infective part of the organism’s life cycle). Sporocysts are very hardy and can survive in the environment for a long time. Infection with cryptosporidium causes the enterocytes to die off. The villi become shorter and can start to adhere to each other leading to a large decrease in the surface area for absorption and leading to malabsorption and diarrhea.

Cryptosporidium sporocysts can be seen on a fecal floatation or fecal smear, but they are small, so you have to carefully look for them. There is no effective drug to kill this parasite. Deccox might have some protective value if started before infection but clinical trials have been inconsistent in showing an effect. Treat supportively, like you would for bacterial/viral diarrhea. Recovered animals are immune to reinfection.

Coccidia:

Coccidia are also protozoan parasites, Eimeria species, and are a significant cause of diarrhea in lambs. Coccidia is important because it has the potential to cause severe scours that can kill lambs and it can also cause severe damage to the GI tract leading to long term poor growth in lambs that recover from the acute infection.

Life cycle: It takes about 21 days from the time a lamb ingests an infectious sporulated oocyst, until that parasite’s offspring reaches an infectious state for the next lamb. The oocyst hatches and releases multiple sporozoites. Each of them enters an enterocyte and divides to form up to thousands of merozoites. The cell is then ruptured and all the merozoites are released into the GI tract, where each one of them invades an enterocyte, they reproduce, rupture those cells and release thousands more merozoites. This cycle repeats a few times and then the merozoites that invade enterocytes start to form gametocytes, which also rupture enterocytes when they produce oocysts. The oocysts are passed in the manure and need moisture to mature into sporulated oocysts that are able to infect other lambs.

Signs: Coccidia cause scours by damaging the GI tract when all the sporozoites and thousands of merozoites rupture enterocytes. The resulting malabsorption as well as bleeding into the GI tract leads to hypertonic GI contents and scours. Scours are often black (digested blood) or can have fresh blood and mucus in it. Lambs have abdominal pain, often straining to pass manure. Lambs with a lot of damage to their Gi tracts become anemic due to blood loss. Severely affected lambs can die from dehydration and blood loss. Very sick lambs that recover can remain stunted due to scarring in the GI tract leading to long term malnutrition. Depending on the age of the lambs and their general health, signs might vary from only slightly loose manure all the way through to multiple dead lambs. Most of the damage is done by immature stages of the parasite, so oocysts may or may not be seen on fecal flotation.

Treatment: Multiple drugs are available to treat coccidia. Most of them are not labeled for treatment of lambs in the U.S., so be sure to talk to your veterinarian about the appropriate dose and withdrawal times when using these drugs.

- Amprolium

(Corid, or generic brands). This drug kills coccidia at higher doses and can be used to prevent coccidia at lower doses. It needs to be given once a day for multiple days. It can be added to drinking water but works better if given as a drench so you are sure each lamb is getting an appropriate dose. The drug kills coccidia by blocking their thiamine receptors and the organism dies due to thiamine deficiency. It also inhibits the development of merozoites. There have been rare instances of polio in lambs treated with Amprolium, so watch for this and have thiamine on hand to treat lambs.

- Sulfadimethoxine

(Albon, or generic brands). This drug is an antibiotic and also needs to be given daily for multiple days to be effective.

- Oregano oil

(Regano). A SARE grant-funded study on using oregano oil as a preventative/treatment for coccidia showed some promise. https://www.mofga.org/resources/sheep/regano/

- Toltrazuril

(Baycox). One dose treatment that works very well BUT is not an FDA approved drug for use in livestock in the U.S.A.

- Condensed tannin feeds (sericea, birdsfoot trefoil). Feeding for two weeks before, until four weeks after weaning is protective. It works well if it makes up a large portion of the diet, but long-term use can lead to mineral deficiencies.

- Coccidiostats

(Deccox, Bovatec). These drugs interfere with the reproduction of coccidia but do not kill the organisms outright. They are FDA approved drugs and are available to mix into feed or minerals according to label instruction. Many commercial creep feeds are sold with coccidiostats already added in. These drugs are best used in the prevention of coccidia by reducing the number of oocysts in the environment. Bovatec is toxic to horses, donkeys, mules as well as dogs; if you use this, make sure to keep it out of reach of your guard animals.

-

Sick lambs also need supportive care.

- Oral electrolytes for dehydration.

- Consider deworming anemic lambs, as even a low grade barberpole worm infection can push these lambs over the edge.

- B Vitamins.

- Clean up the environment – move lambs to fresh pasture or clean out bedding in the barn.

- Antibiotics for severely affected lambs as the gut-blood barrier is damaged.

- Oral electrolytes for dehydration.

Prevention

-

Use coccidiostats at key times.

- Feed to ewes in the last month of pregnancy to reduce shedding of oocysts. (Deccox during this time can help to prevent toxoplasma abortion too.)

- Feed to lambs for 28 days before stressful events like weaning.

- If you are bringing freshly weaned feeder lambs or other young stock into an environment that is contaminated.

- Feed to ewes in the last month of pregnancy to reduce shedding of oocysts. (Deccox during this time can help to prevent toxoplasma abortion too.)

-

Reduce environmental contamination.

- Provide adequate fresh bedding in the lambing area, jugs and lounging areas to minimize contact that lambs have with manure.

- Ideally have less than a 30-day difference in the ages of lambs being housed together.

- Keep lambs from climbing (and pooping) in feed bunks.

- Keep bedding dry.

- Separate sick lambs from others.

- Direct sunlight and drying out will render the oocysts non-infectious, otherwise they can remain viable in the environment for up to a year.

- Provide adequate fresh bedding in the lambing area, jugs and lounging areas to minimize contact that lambs have with manure.

- Keep your lambs healthy and stress free. Make sure your ewes are getting good enough nutrition to support all their lambs. Make sure all lambs have received adequate colostrum.

You will be able to find some coccidia in the GI tract of most sheep if you look hard enough. Sheep with a strong immune system that are not stressed can be exposed to coccidia oocysts and gradually build up immunity, never showing any signs of disease. However, exposing stressed, young animals to large numbers of coccidia oocysts can quickly lead to severe disease and death.

Typically scours are seen in lambs between one and six months old and often associated with a stressful event like weaning, moving to a new farm, bad weather etc. Most outbreaks are in 1–2-month-old lambs that are housed indoors. Older lambs that have never been exposed to coccidia, traveling to a new home (stress) that has high environmental contamination with oocysts can be severely affected.

Coccidia are host species specific – your chickens, calves and dogs that have coccidia will not give your lambs coccidia. Lambs get it from ingesting something contaminated with fecal matter from other sheep.

Sheep have many species of coccidia, some perfectly benign, others very pathogenic (disease causing). Finding coccidia oocysts in a fecal sample of hard pellets from a perfectly healthy, happy sheep does not require any treatment.

Coccidia have a long life cycle, and GI tract damage occurs before the parasite starts producing oocytes. Having a negative fecal sample in a sick sheep does not exclude coccidia as a diagnosis.

Worms:

Gastrointestinal nematodes (GIN) are worms and an important cause of scours and production loss in sheep. Most producers think about barber pole worms (Haemonchus contortus) when the topic of worms comes up as this is a very important parasite of sheep. Haemonchus does not cause diarrhea, so it is not important in the context of scours. We do, however, need to include it here, as it complicates the diagnosis of scour causing worms.

-

Haemonchus contortus:

- On a fecal egg count (FEC) the eggs of all the strongyle worms look the same. Haemonchus and all the GIN discussed below are indistinguishable, so a fecal egg count report that lists xxx eggs per gram (epg) of strongyles could be any of these worms. If you are having trouble with strongyles in your flock it can be useful to have your veterinarian send in a sample for a larval culture to find out which strongyles you are working with, but it is a specialized and expensive test and not required in most cases.

- FAMACHA scoring is a measure of anemia and only works to decide if deworming is necessary for Haemonchus. A good FAMACHA score in a scouring lamb DOES NOT rule out GIN.

- Haemonchus females are much more prolific egg layers than the other strongyles. They produce 5000 – 10,000 eggs each day while the other guys only produce hundreds of eggs per day. This means that for the same epg, you can have 10 times as many adults of the other strongyles. This makes it really hard to base deworming decisions on FEC, as a 500 epg of Haemonchus can be produced by very few worms and not require deworming, while a 500 epg of the strongyles below is produced by many more worms, causing more and ongoing damage that requires deworming.

- On a fecal egg count (FEC) the eggs of all the strongyle worms look the same. Haemonchus and all the GIN discussed below are indistinguishable, so a fecal egg count report that lists xxx eggs per gram (epg) of strongyles could be any of these worms. If you are having trouble with strongyles in your flock it can be useful to have your veterinarian send in a sample for a larval culture to find out which strongyles you are working with, but it is a specialized and expensive test and not required in most cases.

- Teladorsagia circumcinta (Ostertagia, brown stomach worm), Trichostrongylus axei (Stomach hairworm): Both are stomach worms; fourth stage larvae and adults of these species live in the abomasum (stomach). They feed and burrow in the acid producing areas of the stomach, leading to decreased stomach acid production, resulting in maldigestion. Having undigested food present in the lower GI tract leads to excess fluid being pulled into the GI tract, causing diarrhea. Larvae and young adults (not laying eggs yet) already do damage so a negative FEC does not rule out these GIN. Affected lambs have scours and have decreased appetite, over time they lose weight and become hypoproteinemic, leading to bottle jaw. They are typically NOT anemic and have good FAMACHA scores.

- Trichostrongylus colubriformis, T. vitrinus, T rugatus (Black scour worm, bankrupt worm): Larvae burrow under the surface of the small intestine. Young adults hatch out here and do more damage in the process. This damage to the GI lining leads to malabsorption, and unabsorbed nutrients present further down the GI tract pulls extra fluid in and leads to scours. The life stages that cause damage do not produce eggs yet, so a negative FEC does not exclude this parasite. Affected lambs have scours, loss of appetite and weight loss. They are typically NOT anemic and have good FAMACHA scores.

Teladorsagia and Trichostrongylus species do very well in cool, moist environments. The larval stages, on pasture as well as inside the sheep, can undergo arrested development (stop developing into adults if the environment outside is not favorable, and resume when it is better) so you can see overwhelming infections when conditions become favorable.

Scours due to worms affect lambs as well as ewes in late pregnancy and early lactation. Remember a negative FEC does not rule out GIN. Copper oxide wire particles (COPW) are an effective dewormer only for Haemonchus and are NOT effective against these scour-causing worms. Adequate protein in the diet of lambs and pregnant/lactating ewes has a protective effect against GIN.

We all want to preserve the efficacy of dewormers to kill GIN when we need them; unfortunately, this leads to some shepherds not using them when they are needed. Remember, the larvae of these worms cause disease even if they are not producing eggs yet so you can have significant disease and negative FEC. I am not advocating deworming all your lambs, nor scheduling deworming dates but I strongly recommend deworming actively scouring lambs. Remember, not deworming 20% of your lambs leaves adequate refugia to prevent dewormer resistance. Hopefully a much smaller percentage of your lambs are having scours at the same time.

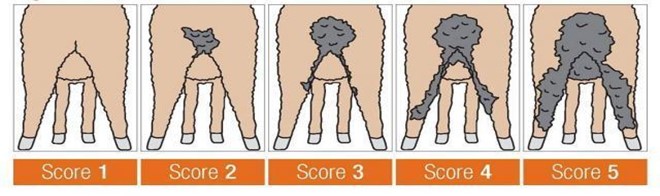

Larval hypersensitivity scouring:

Sheep that are parasite resistant mount an immune response to the parasites and through several different methods make their GI tracts an undesirable place for worms to live and reproduce. Interestingly, some sheep can have severe diarrhea due to a suspected allergic response to GIN, usually to the ingested larvae and not adults. These animals have very low or negative FEC with ongoing diarrhea. Australian researchers have identified a phenomenon called “winter scours” caused by some sheep reacting to infection with very low numbers of Teladorsagia larvae. Studies are still being done to find out what exactly causes this hypersensitivity to worms in some sheep. Deworming and selection for parasite resistance is not effective in preventing winter scours. They recommend selection against sheep that display winter scours (do not retain affected ewe lambs and do not use affected ram lambs). Australia has an EBV for dag scoring (a measure of the degree of soiling on the back end of animals) that helps with this selection. A study was done that showed that fecal moisture and dag score are correlated traits and that dag score is 12-16% heritable. Of course, this research was done in a different country and not on Katahdins, but keep this in mind if you have parasite resistant sheep with multiple negative/ low FEC that have continual or long-term intermittent scours.

Using the Five Point System when deciding which animals require deworming instead of just FAMACHA scoring will help identify and treat animals affected by all classes of GIN. https://www.wormx.info/_files/ugd/6ef604_257994a38215450eb936111fadfebbda.pdf

There is a lot of information about prevention and treatment of GIN available; wormx.info is a great resource.

Diet

A lot of research is being done on the importance of the microbiome (the organisms that live on the skin, respiratory tract as well as GI tract of people and animals) in maintaining health. Experimentally, diseases have been treated successfully just by adding GI microbes from healthy animals to the GI tract of affected animals. Many pre- and probiotics are already on the market and there is a lot of ongoing research in using microbiome alterations in the prevention and treatment of disease. Diet has a huge effect on the composition of the GI microbiome and abrupt changes in diet will alter the microbiome. Any change in diet can cause transient diarrhea in sheep.

Animals on Pasture:

- Changing from one pasture to the next can be a significant diet change if the pastures contain significantly different plants.

- Spring flush pastures have high protein and energy, combined with low fiber in the fast-growing plants. Changing from hay feeding to this hot ration in the spring is pretty much guaranteed to cause scours.

- Rain after a period of drought has a similar effect as the spring flush.

- Sheep might ignore a specific plant when it is mature but overgraze it when immature.

- In times of drought, animals might eat plants that contain GI irritants like Iris that they usually have the good sense not to eat.

Grain feeding:

- Rumen bacteria need time to adjust to different feeds. Make changes slowly.

- Start feeding grain to pregnant sheep slowly and gradually increase to the full amount over multiple days. If you increase grain for lactating ewes, also slowly increase the amount fed.

- Watch if you change groups, especially moving ewes to smaller groups. Timid ewes that were bullied in the large group and did not get their share of grain can get acidosis if they are suddenly able to get their whole share in the smaller group.

Rumen acidosis – grain overload:

The rumen functions best and is able to support cellulose digesting flora when it is kept at a neutral pH. Ingestion of large volumes of easily digested carbohydrates can rapidly change the rumen pH to be acidic. Lactic acid producing bacteria thrive on easily fermentable carbs and the lactic acid they produce decreases the pH in the rumen. Low rumen pH favors the growth and maintenance of lactic acid producing bacteria, increasing their population, while inhibiting the growth and (if severe) killing off of other flora that prefers a neutral pH.

Rumen acidosis can be life threatening if severe:

- Increased lactic acid in the rumen is osmotically active and draws large volumes of fluid into the rumen. This, combined with the animal feeling sick and not drinking, leads to dehydration, which can lead to kidney failure and circulatory collapse.

- Some of the bacteria that are killed by the low rumen pH are endotoxin producing bacteria. When these bacteria die and are broken down, they release endotoxins that cause inflammation, fever and shock.

- The acid environment damages the rumen epithelium, disrupting the normal function of the gut-blood barrier. This allows the entry of bacteria into the bloodstream that can lead to sepsis and/or liver abscesses. Severe rumen damage can cause leakage of rumen contents into the abdominal cavity and cause peritonitis (infection of the lining of the abdominal cavity).

- The change in rumen flora can lead to polioencephalomalacia (thiamine deficiency) if there is overgrowth of thiaminase (enzyme that breaks down thiamine) producing bacteria.

If you find one (or multiple, if you are unlucky) animals with the symptoms below, you should be suspicious of grain overload. Check your grain supplies, did the sheep break into the foodshed and eat a bag of chicken feed? Did the kids have friends over and feed a whole loaf of bread or box of crackers to the friendly lamb? Did a ewe break into the creep feeder and clean it out? Symptoms of grain overload include:

- Not eating

- In good body condition and healthy with good appetite until very recently

- Acting sick (not getting up, grunting, kicking at their bellies, depressed)

- Dehydrated

- +/- fever

- Having diarrhea, usually sour smelling and could have pieces of grain in it

- Worst case: dead animals with acidic (pH <5.5) rumen contents.

Identifying and treating grain overload early is important. Severely affected animals might die in spite of aggressive treatment. If at all possible, get your veterinarian involved. This is a serious problem.

- DO NOT GIVE ANYTHING THAT WILL SLOW DOWN DIARRHEA. In this case the GI contents are much better out than in.

- If you are sure that it is grain overload, you can give oral magnesium hydroxide (Magnalax) or milk of magnesia. It is an antacid and mild laxative. It will help to increase the rumen pH and help to move the GI content out. Do not give this if you are not sure that your animal has grain overload, otherwise you will change the rumen pH to alkaline and that will also lead to suppression of rumen protozoa and interfere with the normal rumen flora function.

- Your veterinarian can do a rumenotomy or rumen lavage to remove the grain and replace it with rumen contents from an unaffected flock mate. Bicarbonate containing IV fluids can be administered to correct dehydration and acidosis.

- Antibiotics are indicated to prevent sepsis in cases where disruption of the gut-blood barrier is suspected.

- Do not offer any grain, hay only.

- Give thiamine to prevent polio.

Obviously, this problem will affect animals to different degrees depending on how much grain they consumed. As soon as you find out that your animals have overindulged in grain, talk to your veterinarian and be sure to provide:

- How much grain was eaten;

- Type of grain – milled grains can cause more severe disease than whole grains;

- What your animals’ normal diet is (animals that eat more grain in their normal ration have a higher tolerance for grain overload).

Your veterinarian should be able to advise you on how aggressive the treatment needs to be.

Unweaned lambs:

Diet is an important cause of scours in bottle lambs, but is not often a problem for dam reared lambs. Dam reared lambs eat small meals often. Lambs initially only use their abomasum for digestion and have an abomasal groove, a fold in the walls of the rumen and omasum, which is activated by suckling. The abomasal groove bypasses the first three stomachs so milk is directly deposited in the abomasum for digestion. Correct neck position when nursing plays a part in enabling the groove to close. When the groove does not close milk goes into the undeveloped rumen and ferments there, interfering with the normal digestion as well as predisposing the lamb to bacterial scours.

Inadequate calorie intake is a major stress on a young lamb. Dams that do not have enough milk for all their lambs or that get mastitis and do not let them suckle have lambs under nutritional stress. Not increasing the amount fed adequately as bottle lambs grow also puts them under nutritional stress.

Dam reared lambs have an advantage over artificially reared lambs due to a more appropriate diet and a feeding mechanism that is more protective to bacterial overgrowth. With that being said there are many producers out there that do a great job raising healthy lambs artificially, there are just some things to keep in mind to make it go smoothly.

Dam reared lambs:

- Milk in the udder is sterile (unless the ewe has mastitis).

- Bacteria can invade into the teat canal and reproduce there; however, lambs suck frequently so bacteria do not have enough time to reproduce out of control before being ingested by the lamb.

- The ewes’ teats can be contaminated by bacteria and lambs do pick up infection this way. However, there are lots of non-pathogenic bacteria on the skin too, and they all compete for resources so in general there are not very large doses of bacteria ingested this way.

- Wooly ewes with scours that contaminate the wool surrounding their udder can be a significant source of infection for their lambs, if the lambs suckle on the contaminated wool. If you have wooly ewes crutching (shearing under the tail and around the udder) pregnant ewes can prevent this problem.

- Lambs consume small meals at a time so there is not a very large volume of milk in their GI tract at a time to allow out of control bacterial overgrowth.

- The ewe transfers beneficial flora to her lambs by close contact and licking behavior around lambing time.

Artificially reared lambs:

- Milk replacer is (hopefully) mixed in clean and even sanitized equipment but is not sterile.

- Milk replacer quality is important. Replacer with protein from milk will be easier to digest compared to replacer with protein from soy. Easier digestion leads to less undigested milk passing further down the GI tract, so there is less opportunity for pathogenic bacteria to feed and grow. Lambs are able to absorb more nutrients so will be under less nutritional stress than lambs fed replacer with soy protein.

-

Milk replacers with acidifying agents (or adding yogurt) have a less favorable pH for overgrowth of pathogenic bacteria. Active culture yogurt also introduces beneficial bacteria to compete with the pathogenic bacteria.

Bottle feeding:

- Read the instructions and weigh your lambs. Make sure you do not over- or underfeed them. Work out the volume needed per day and divide it into as many meals per day as you are able to feed. Weigh lambs at least weekly to make sure they are growing and adjust the amount fed as they are gaining weight.

- Be sure to mix at the right ratio of replacer to water every time. Hyperosmolar formula will pull excess fluid into the GI tract. Adding too much water makes it less nutrient dense and lambs will not receive all the nutrition they need leading to nutritional stress.

- Ideally only mix as much as the lambs will eat in a meal. Feed the leftovers to the dogs, chickens or pigs. Milk replacer is expensive and we all hate to waste it, however, feeding leftovers at the next meal is risky. Consider this example: You mixed the formula and it started out at body temperature. You probably kept it at that temperature (tucking it under your arm or in your overalls) while finding the lambs and feeding them. You probably did one or two more things while you were in the barn anyhow before you got around to putting the replacer in the fridge. The lambs suckled on the bottle, introducing bacteria into the milk replacer. Remember refrigeration slows down the growth of bacteria, it does not kill them. When you re-heat the formula the bacteria that started growing before just continues. Worst case, you added the leftover to some freshly mixed formula and you have leftovers again, treating them in the same way. This is a really good way to lose lambs to bacterial scours or clostridium

- Wash your equipment promptly with soap and hot water, bacterial biofilms can form in your bottles and teats if you let them sit for extended periods of time before washing.

- Hold the bottle so the lamb drinks in a position resembling drinking from their dam. Improper position can cause the abomasal groove to not close properly.

Bucket feeding cold:

- Cold bucket feeding should have milk replacer that is cold enough to give the lambs brain freeze if they overindulge, and the milk should never run out. The idea with this is to mimic the smaller, more frequent meals dam reared lambs have.

- Milk replacer should be mixed with near body temperature water (use the temperature according to the instructions for the brand you are using), so it starts out at an ideal temperature for bacteria to grow. If bucket feeding cold milk, make sure you cool the replacer down as quickly as possible to reduce the time it spends above 40’F. Mix up a fresh batch at least twice a day. Have two containers so you can replace one with a fresh bucket when it gets close to empty. Make sure it stays cold the entire time lambs have access to it. Make sure you have enough nipples and that there is always milk replacer available so that lambs do not feel they need to compete and overindulge.

- Take buckets apart and clean everything thoroughly with warm soapy water at least once a day.

Bucket feeding warm milk:

- Same rules as bottle feeding.

- It is important to have enough nipples so everyone can drink at the same time. If they bump each other off the nipples and stand on their heads and assume all kinds of strange body positions to drink, it can lead to the abomasal groove not closing and replacer ending up in the rumen rather than the stomach.

Milk machines (Lak-Tec):

- This is the closest you can get to the normal feeding schedule of a dam reared lamb.

- Milk replacer is mixed on demand so it does not sit at body temperature for extended periods of time.

- You still need to pay attention to proper cleaning and functioning of equipment.

- These are expensive machines so farms are more likely to have lambs of different ages combined in a group if your lambing window is not tight. Older lambs are more likely to have built up immunity to parasites and microbes so they are not affected, but they still shed them and younger lambs are susceptible. Ideally you should not have a larger than 30-day age difference between lambs that are housed together.

- Read the instructions and weigh your lambs. Make sure you do not over- or underfeed them. Work out the volume needed per day and divide it into as many meals per day as you are able to feed. Weigh lambs at least weekly to make sure they are growing and adjust the amount fed as they are gaining weight.

Antibiotics:

Antibiotics have a spectrum of bacteria that they kill or prevent from reproducing, however all antibiotics will negatively affect beneficial bacteria too. Fungi, viruses and protozoa are not affected by antibiotics so you can get overgrowth of these organisms as the beneficial bacteria are not there to compete with them.

- Do not use antibiotics if they are not necessary.

- Give probiotics during and/after antibiotic use.

Minerals:

Minerals are important for the general health of your animals. Soil in different areas of the country is deficient in different minerals, so you need to use mineral supplements that are appropriate to your location. Remember, if you get your hay or grain supplements shipped in from a few states over, the mineral contents may be vastly different from local products. Having minerals analyzed from a liver sample of a healthy slaughter animal is a good way to see what the mineral levels in your flock are. Adequate zinc, copper & selenium are important for good immune function. Sheep do need copper but too much will kill your sheep. Stored forages (hay) quickly lose their vitamins in storage, so it is good practice to add Vitamins A and E to your ration in the non-grazing season.

Water:

Water can be a source of bacteria and toxins if contaminated. High levels of iron and sulfur in water can bind minerals and decrease availability to the sheep. Keep water clean and fresh. Keep troughs so that waterfowl do not bathe in them and animals cannot step in or poop in them. Have a plan on how to drain them without making a mess if needed.

Water can be a source of bacteria and toxins if contaminated. High levels of iron and sulfur in water can bind minerals and decrease availability to the sheep. Keep water clean and fresh. Keep troughs so that waterfowl do not bathe in them and animals cannot step in or poop in them. Have a plan on how to drain them without making a mess if needed.

Stress

Stress really wreaks havoc on the normal functioning of the GI tract. A lot of studies have been done in piglets showing that the villi become shortened and digestion is adversely affected by just the stress of weaning without adding any disease. Cortisone depresses the immune system. Any event that causes stress for sheep will affect their GI tract, suppress immunity and predispose them to all the other causes of scours.

Artificial rearing:

How did this lamb become a bottle lamb? Was the lamb rejected and bullied by mom, or was it a triplet or quad outcompeted by siblings? Did the dam have mastitis? Did you find it cold and unresponsive but were able to nurse it back to life? These lambs had a rough start to life and lots of stress already. Keep them warm, minimize competition for food, watch them closely for any signs of disease and treat them ASAP.

Dam reared triplets/quads:

Three or four lambs competing for two nipples is stressful. If the ewe does not quite produce enough milk for all three/four there will be stress due to malnutrition too. Watch these lambs, to be sure one isn’t falling behind. Offer a supplemental bottle feeding if needed.

Weaning:

Weaning is always super stressful for lambs. Try to keep the rest of their routine as familiar as possible. They are losing milk from their diet, so do not change anything else in their diet at the same time. Although it is convenient to do vaccines and other management tasks like fecal collection at the same time, it is better for the lambs to just do weaning on that day and not add additional stress.

Moving to a different farm:

If at all possible do not buy lambs directly at weaning. If they can have two weeks or so to get over the stress of weaning before adding the stress of moving there is a lower chance of disease happening.

Pregnancy & Lactation:

Large demands on the ewe due to supporting fast growing lambs in the last four weeks of gestation, combined with decreased capacity for feed consumption due to the lambs taking up space in the abdomen creates stress. Lactation is the highest nutritional demand stage for a ewe. Make sure to offer adequate nutrition and minerals to ewes in these stressful times; watch them carefully for disease and treat them early.

My sheep has scours, now what?

The table below shows the most likely causes of diarrhea by age group. I am sure that other causes have and will happen, so be sure to check with your veterinarian if this does not seem to apply to your situation. Refer back to the information above for more information and suggestions on treatment and prevention of different classes of causes.

| Age Class | Probable Cause | Actions |

| < 3 Weeks | Dam Reared

Artificially Reared

|

|

| 3 Weeks – 2 Months |

Dam Reared

Artificially Reared

|

|

| > 2 Months |

|

|

| Adults |

|

|

By: Isabel Richards, EAPK Communications Committee

References

https://opentextbc.ca/biology/chapter/22-1-osmoregulation-and-osmotic-balance/

Digestion and absorption

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1357153/?page=1

https://www.journalofdairyscience.org/article/S0022-0302(85)81011-0/pdf

https://www.intechopen.com/chapters/71844

http://www.vivo.colostate.edu/hbooks/pathphys/digestion/smallgut/absorb.html

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4672224/

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7868804/

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9564998/

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8697929/

https://www.journalofdairyscience.org/article/S0022-0302(08)71245-1/fulltext

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5994371/

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9609858/

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4867772/

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9680619/

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9197122/

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8714829/

https://ohiostate.pressbooks.pub/vethisto/chapter/8-small-intestine/

Bacteria and viruses

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7125768/

https://europepmc.org/article/MED/29275032

https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/104063870802000301

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9609858/

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0749072008000996#bib2

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0022030217302977

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0749072015313025?via%3Dihub

Parasites

https://cms.galenos.com.tr/Uploads/Article_22579/TPD-28-15.pdf

https://content.ces.ncsu.edu/coccidiosis-the-most-common-cause-of-diarrhea-in-young-goats

https://www.nadis.org.uk/disease-a-z/sheep/coccidiosis-in-lambs/

http://www.animalscienceconference.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/2021AAAS_McMillan_Aaron.pdf

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8828848/

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32447149/

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9550700/

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7726760/

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10480726/

http://tools.wormboss.com.au/sheep-goats/worms/roundworms/black-scour-worm.php

http://www.aaabg.org/aaabghome/AAABG23papers/29McMillan23115.pdf

https://www.agric.wa.gov.au/genetics-selection/sheep-worms-%E2%80%93-breeding-worm-resistant-sheep

Illustration of dag scoring system

https://www.agric.wa.gov.au/livestock-parasites/managing-flystrike-sheep?page=0%2C1

Stress

https://journals.physiology.org/doi/full/10.1152/ajpgi.00197.2006#R39

https://www.nature.com/articles/pr200618

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4867772/

Diet

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9332062/

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2770524/

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9781347/

![]()